Holodomor through the eyes of a Berkeley professor and a Canadian Jewish woman

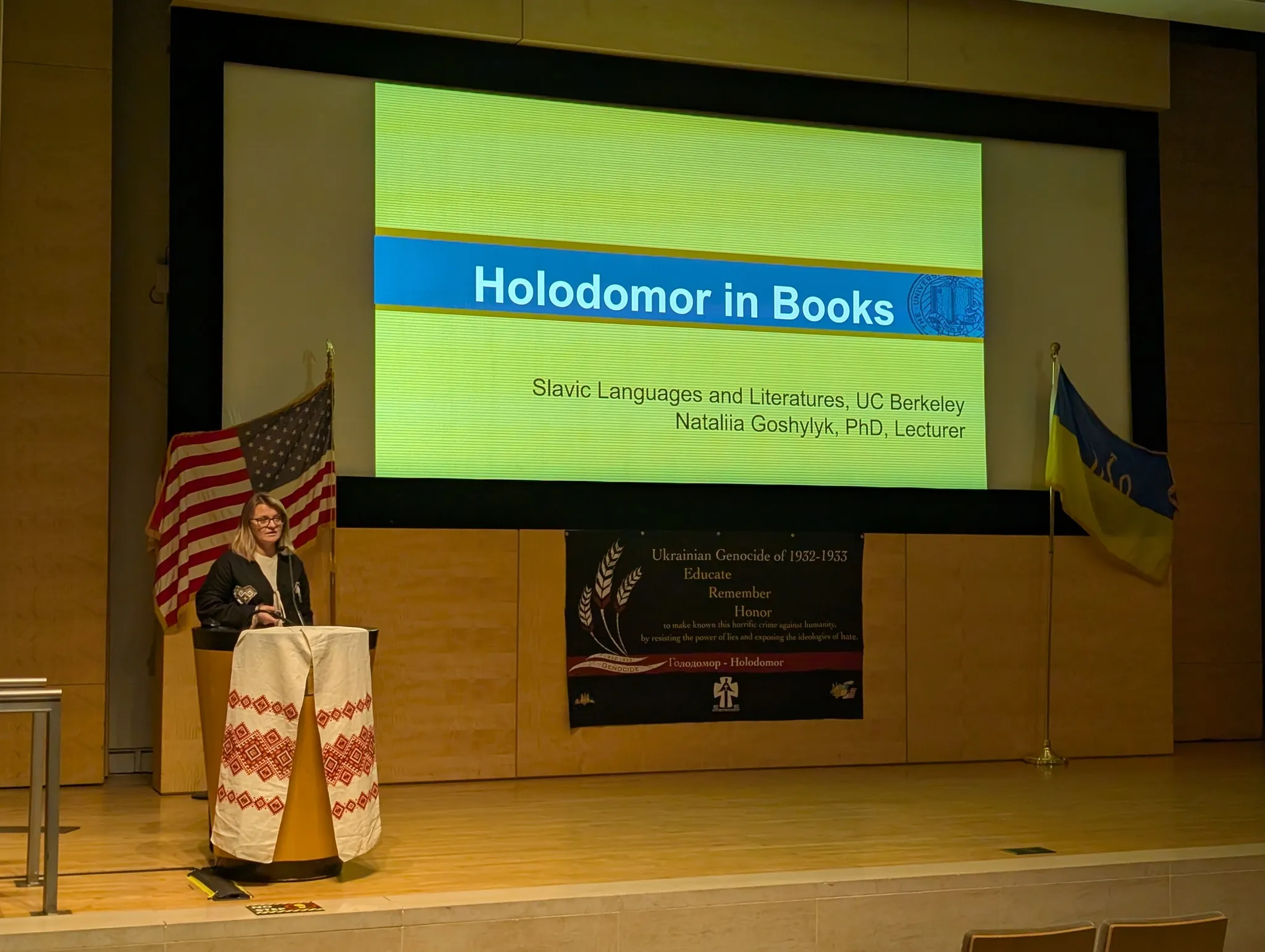

On January 15, the 92nd anniversary of the Holodomor-genocide of the Ukrainian people was commemorated at the Central Library of San Francisco. Associate Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Natalia Hoshylyk, spoke at the event, followed by a screening of the documentary film “Hunger for Truth.”

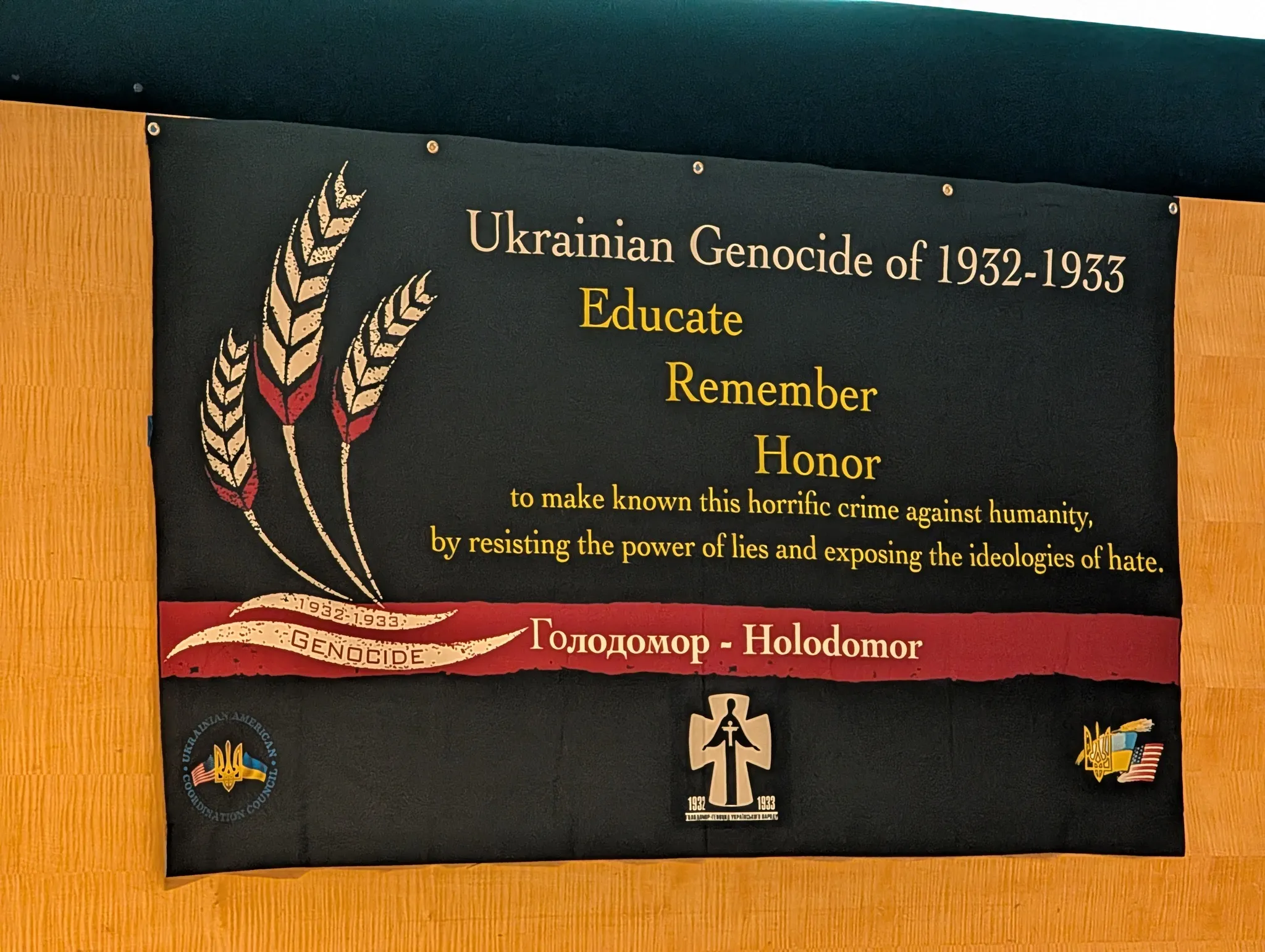

The event was organized by the California branch of the Ukrainian-American Coordinating Council (UACC).

In the opening remarks, the head of the library's foreign literature department, Mykhailo Pashkov, and the event organizer from UACC, Maria Cherepenko, thanked the library for annually providing a venue to honor the memory of the Holodomor victims since 2010.

This tradition was founded by San Francisco Ukrainian community activist Nadia Derkach, who, unfortunately, has passed away. However, the cause she initiated continues to live on.

The speakers emphasized that any mention of the Holodomor in the USSR was strictly forbidden. Even in the free world, many who lived through those events did not have the strength to speak about them.

"My father, who survived the Holodomor, never spoke about it," shared Maria Cherepenko.

The Consul General of Ukraine in San Francisco, Dmytro Kushneruk, also spoke. Professor Natalia Hoshylyk presented an overview of new fiction and documentary books about the Holodomor. She paid special attention to publications for children and teenagers, as family stories and fictional narratives help the younger generation understand

the tragedy of their people. Among the presented books were "Grandma's Chickens," "Tell Me a Story, Grandma," "Threads: Zlata's Ukrainian Shirt." Many publications are available in both Ukrainian and English.

The professor also presented a series of books for adults: the documentary research by renowned American historian Anne Applebaum, Red Famine, memoirs by Erin Litteken — The Memory Keeper of Kyiv (2022), Cynthia LeBrun — Black Sunflowers (2024), the psychological novel by Tanya Pyankova "The Age of Red Ants" and others.

All speakers emphasized the clear connection between the Holodomor and the current aggressive war that Putin's Russia is waging against Ukraine. Like the Soviet empire, the modern Russian government seeks to break the Ukrainian people for their resilience, desire for freedom, and unwillingness to be absorbed by the empire.

This parallelism is vividly revealed in the documentary film Hunger for Truth, presented during the event. The film is based on materials by Canadian journalist Rhea Clyman — a Canadian Jew who became one of the first North American reporters to show the world the true face of the "Soviet paradise" and the tragedy of the Holodomor.

Born in Poland to a Jewish family, Rhea emigrated with her parents to Canada as a child. In 1928, at the age of 24, she traveled to the USSR, captivated by propaganda stories. Initially, she worked as an assistant to New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty, who praised the Soviet system. However, what she saw in the USSR fundamentally changed her perspective.

The brave journalist traveled across the USSR, trying to uncover the truth about living conditions. After visiting the North and seeing the prison city of Kem, she published an article with the telling title: "The Prison City Where No One Laughs."

In 1933, she and her American friends traveled south to Ukraine. Kharkiv, then the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, greeted them with endless queues and a lack of food. Outside the city, the journalists saw desolate villages, abandoned houses, and starving people. The peasants begged them to convey their words to the authorities: "Our children are eating grass because we have been left with nothing."

One woman undressed her children, showing their swollen bellies and thin legs due to hunger. "They took everything from us," they said.

In the film, footage from the 1930s intertwines with modern times. In particular, it features the story of Serhiy Glondar, a Ukrainian soldier captured in Donbas and released only in 2020.

In the film, scholars explain the context of the policies of that time: collectivization,

forced confiscation of property, the extermination of Ukrainian peasantry labeled as "kulaks," — all part of a deliberate policy to break the Ukrainian nation after the defeat of the Ukrainian People's Republic in 1922.

After traveling through Ukraine and Kuban, Rhea Clyman was arrested and deported from the USSR for her revealing articles. Upon returning to Canada, she continued to write the truth and later traveled to Germany, where she witnessed the rise of the Nazi regime and survived "Kristallnacht."

Her life was filled with courage, but after a severe plane crash, she no longer traveled. She spent the rest of her years in New York, where she died in 1981.

The film also tells the story of the NKVD cases against Mykola and Kosti Bokany, who created a family photo album during the Holodomor. These materials were declassified in independent Ukraine.

Director Andriy Tkach created a profound portrait of an outstanding journalist and at the same time — a historical canvas connecting Stalin's Holodomor and the modern Putin war.

"It is quite challenging to find a short English-language film about the Holodomor that could be shown at such events," noted Maria Cherepenko. Hunger for Truth is precisely such a film. It deserves the widest distribution — not only within the Ukrainian community but far beyond it.

Photo credit: Ukrainian American Coordinating Council, San Francisco, CA